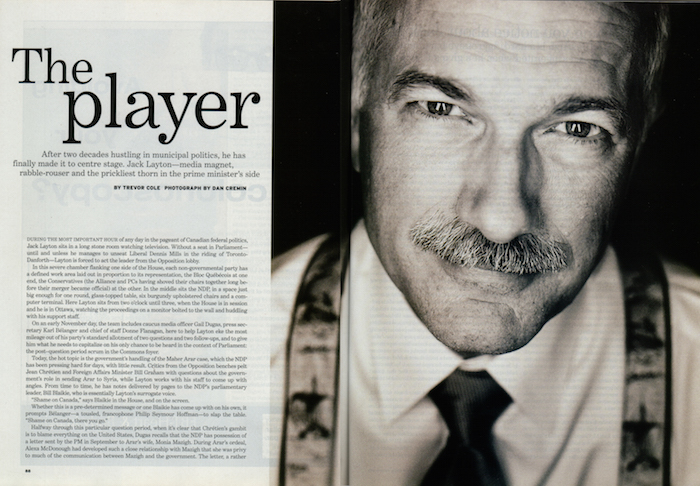

THE PLAYER

A profile of the late NDP leaderBy Trevor Cole

(Originally published in Toronto Life magazine, APRIL 2004)

On an early-November day in Ottawa, the nation's capital is shrouded in a frozen mist. The sidewalks are glazed with ice and the airwaves are filled with talk of Mahar Arar, the Canadian whose story of deportation by American officials and torture by Syrian has just come fully to light. The combination works to make the landscape of Parliament Hill seem measurably more hazardous than usual. This is a day for picking one's way carefully, and yet, a little while before Question Period, there's Jack Layton, marching surefooted as ever up the slippery path to work.

He pauses outside the Parliament Buildings to check his Blackberry, mocks his two staffers—communications director Jamie Heath, and chief of staff Donne Flanagan—who've grabbed the opportunity for a quick cigarette ("I take some pride," says Jack, mirthfully, "in the fact that I was responsible for the first city legislation that made people like you stand outside to smoke"), then he watches as a deadly sheet of ice slides down from the copper roof and smashes right next to them.

"See?" says Jack. "God is punishing you."

Heath and Flanagan, puffing grimly on, seem not at all surprised. If there is some skewed force in the air this particular day, it is not working on behalf of the NDP. Since Layton became leader last January, the party has generated a steady stream of flattering publicity—membership is up, caucus is united and party spirit is buoyed. But today, it's as if things had been going too well, and now it's payback time. Inexplicably, in the matter of Mahar Arar, the party's publicity stream has dried up, leaving it with no leverage at just the moment when the Chrétien government appear vulnerable.

At the morning staff meeting, Heath, who makes you think of a young and somewhat annoyed Fred Astaire, announced his frustration. "The Globe and Mail has three pages today on Arar," he told the gathered staffers, as well as Layton. "We're the only party that asked a question, we asked the lead question yesterday and we asked a supplementary yesterday on Arar. But we are not in these stories. We are simply not."

This afternoon, Jack's job is to make it past the icy obstacles, and change that.

[linespace]

During the most important hour of any day in the stagey pageant of Canadian federal politics, Jack Layton sits in a long stone room, watching television.

Without a seat in Parliament—until and unless he manages to unseat Liberal Dennis Mills in the Toronto riding of Danforth-Riverdale—Layton is forced, during Question Period, to act the leader from the opposition lobby. In this severe chamber flanking one side of the House, each non-governmental party has a defined work area laid out in proportion to its representation, the Bloc Québécois at one end, the Conservatives (the Alliance and PCs parties having shoved their chairs together long before their merger became official) at the other. In the middle sits the NDP, allotted an area big enough only for one round, glass-topped table, six burgundy-upholstered chairs, and a computer terminal. Here Layton sits from two o'clock until three, when the House is in session and he is in Ottawa, watching the proceedings on a monitor bolted to the wall, and huddling with his support staff.

This day, the team includes caucus media officer Gail Dugas, press secretary Karl Belanger, and Donne Flannagan, chief of staff, there to help Layton eke the most mileage out of his party's standard allotment of two questions and two supplementals, and to give him what he needs to capitalize on his only chance to be heard in the context of Parliament—the post Question Period scrum in the Commons foyer.

Today, as expected, the hot topic is the government's handling of the Mahar Arar case, which the NDP has been pressing hard for days with frustratingly little result. Critics from the opposition benches pelt Chrétien and Foreign Affairs minister Bill Graham with questions about the government's role in sending Arar to Syria, while Layton works with his staff to come up with angles. From time to time, he has notes delivered by pages to Parliamentary Leader Blaikie, who is essentially Layton's surrogate voice.

"Shame on Canada," says Blaikie in the House, and on the screen.

Whether this is a pre-determined message, or one Blaikie has come up with on his own, it prompts Belanger—a tousled, Francophone Phillip Seymour Hoffman—to slap the table. "Shame on Canada, there you go."

Halfway through this particular Question Period, when it's clear that Chrétien's gambit is to blame everything on the United States, Gail Dugas recalls that the NDP has possession of a letter sent from Chrétien to Arar's wife, Dr. Monia Mazigh, in September. During Arar's ordeal, Alexa McDonough had developed such a close relationship with Mazigh that she was privy to all communication between Mazigh and the government. The letter, a rather mild assurance of the government's interest in the case, bears no hint of complaint about the Americans. Doesn't even mention them. Where was his outrage then? Layton will demand. This could work.

In the House, with about 15 minutes to go before the hour is up, Chrétien fulminates with outrage over the unconscionable actions of the Americans. A flurry of communication between the NDP team in the lobby and the staff back at party headquarters a few blocks away has seen to it that Layton now has a copy of the Prime Minister's letter to Mazigh in hand. Leaning back contemplatively in his polished wood chair, he looks pleased. "Chrétien is painting himself into a corner here with his outbursts."

In the ornate foyer of the House of Commons, reporters and camera crews gather very much like pods of dolphins waiting to be fed. Three "pools" are set up—that is, three standing microphones at the small ends of funnel-shaped camera lanes marked by queue dividers—supposedly one for Liberal MPs, one for opposition MPs and one for the Prime Minister, although because Chretien has never liked engaging in scrums, his microphone tends to be up for grabs.

The closer it gets to three o'clock and the end of Question Period, the busier the foyer becomes. Stars of the parliamentary bureaus stalk the inlaid marble floor under arches of intricately carved stone, cameramen set up their little stepladders, and the media wranglers, the party press secretaries, begin their work.

In the opposition lobby, Layton circles the date at the top of his copy of the letter, September 4, and makes a note or two on the back. When Bill Blaikie leaves his Commons seat at one point, emerges through one of the doorways and comes down the steps to the NDP table, he sees the letter in Layton's hand and points at it knowingly. "He doesn't blame the Americans in that letter, does he." Then the two of them sit together and confer with Donne Flanagan, and the sense builds that things are proceeding exactly as Jack Layton would wish.

When some people call Layton "media-savvy," they mean it as a synonym for "glib," a way of describing his confidence in front of a microphone, his palpable joy at having an audience. But there's more science to what Layton does than simply looking handsome and dishing out sound bytes. To take one example from his council days, during the Adams Mine debate, Layton was trying to stop the city from filling what had become a lake with trash, and being media-savvy meant carefully positioning himself as the problem solver, not the critic. Northern residents were bussed in to present what Olivia Chow terms "the negative piece"—the worries about ground water and other effects. Layton then appeared, like a miracle, and offered the solutions, the alternatives—"the positive."

But to many of his colleagues on city council, it too-often boiled down to Layton being a camera hog, soaking up the attention that was rightly due others. It wasn't a matter of jealousy, says councilor Pam McConnell, one of Layton's left-wing allies. But "when people have worked on something for a long time and if someone else's name gets attached to it, that's a bit up your nose."

Former Layton staffer Peter Zimmerman offers a simple defense: Layton knew, better than most on council, how to give the media what it needed. But he admits, "Occasionally you'd get the sense that there was frustration."

In his early days as NDP leader, Layton's habit of jumping into the opposition pool before Question Period had barely ended was denounced by other parties as just more of his typical mic-hoggery. But in fact it was Karl Belanger who was behind the strategy. "We needed to establish that Jack not being in the house won't be a factor," he say. "And therefore we were coming out first in the scrums to make him available to the media, so they were seeing him as a player. And it worked; he got a lot of media. And that's why he got flak from the other parties, because our strategy was working."

Over the months that followed, Belanger gradually shifted to a wait-and-see approach, letting government ministers take the lead at the mics and watching as the packs of media divided and settled around specific issues, while Layton lingered in a transition zone between lobby and foyer, by a bust of Agnes McPhail, ready to spring out at his press secretary's signal.

At a few minutes past three, this is where Layton stands, biding his time.

[LINE BREAK]

If ever there was a politician ready for the national stage, it's Jack Layton. After two decades in municipal politics, failed campaigns for mayor of Toronto and two federal seats, and a life spent in service to causes at the fringes of popular debate, he may have seemed to casual observers like a surprise victor in last year's NDP leadership contest. But he trounced his rivals—party heavyweights like Bill Blaikie and Lorne Nystrom among them—because NDPers sensed he could take a party wobbling on the lip of humiliation and instill in it something new, a bit of his ladies' man self-assurance perhaps, some of his persuasive flair. Merely to do that would have seemed enough, and yet, in 15 months, Layton has done far more. He has grabbed the opportunity of a confused leadership on the right and made his party the nation's functional opposition, in the process taking himself closer than he has ever been to the juicy hot zone of influence. That, and not power, Layton knows from experience, is really what matters. As an activist for the environment, an advocate for the homeless and a council seat holder nominally in service to the ratepayers he represented, he has never held any real authority other than moral. But that has never stopped him from maximizing the resources available to him and pushing his agenda.

One night last fall, during the short time I was with him, Layton demonstrated his peculiar ability to maximize his time and resources when he squeezed the following into a few spare hours: an extended stretch of canvassing on behalf of Paula Fletcher who was running (and won) in Layton's old Toronto-Danforth ward. Repeated cell-phone calls during the canvassing, puling him away to private confabs under trees and around corners and frustrating his friend, MPP Marilyn Churley. "Come on, Jack!" Sigh. Grimace. "That's what happens when you go canvassing with the leader of the party." A private huddle with Churley in her red Toyota Solara. A discussion with one of his Ottawa organizers about an upcoming meeting (successful) with Anna Porter regarding the possible publication of his next book. A glass of very nice Henry of Pelham cabernet back at Jack's large, homey Huron Street semi. Some Cantonese chitchat with his mother-in-law. A review of the next day's speech at a luncheon sponsored by the Institute for Research on Public Policy, sent to him on his Blackberry by communications director Jamie Heath. ("Goody," he says, reading.) A flying-thumb rewrite of a couple of crucial points. An energetic rendition of the "Dominion March" on an old pipe organ that Layton, as a teenager, once dismantled and rebuilt. A short conversation, in perfect meowese, with his cat. An earnest explanation of why there is a six-foot-tall painting of his very own head and shoulders leaning against the wall of his living room (lack of storage space) and why this portrait seems reminiscent of the strident official images of Chairman Mao (it was painted by a Chinese artist trained in the same Socialist Realism style that produced those images). After all this, dinner.

A man primed to maximize must of necessity always be "on," and among the first things you notice about Jack Layton, besides his nut-cracker handshake, is the actorly way he moves and speaks, the dashing courtliness of his manner, as if he might have just stepped off the boards of a Victorian melodrama and hadn't quite shed his character. Whether he's seated or standing his back is supernaturally straight. Even in casual conversation, his timing is conscious, his phrasings crafted for emphasis and sometimes overly ornate. "There is," Jack will say, in reference to some mutual understanding, "a complementarity to our discussions." His laugh is a hard, aggressive bark, and when he's forcing his points, advancing his agenda, he has an air of the smarty-pants about him, which is exaggerated when he takes the stage for a speech, and his chin juts righteously and the momentum of the points he makes often lifts him onto his toes. "He taught at the U. of T., he taught at Ryerson," says Toronto councilor Kyle Rae, "so there was this pedagogical attitude he could often take in the debates on council, which people didn't like. They thought they were being talked down to." But even those who find themselves irritated by some of Layton's mannerisms, by his lack of humility, are never left doubting his conviction or his passion. And these are likeable qualities.

University of Manitoba poli-sci professor Geoff Lambert might have said it most succinctly to the Regina Leader Post: "He's sort of a big mouth and a know-it-all, but he's a rather attractive figure."

Attractiveness has something to do with virtue, arguably, and more than any other leading national politician, Layton seems to have some claim on rectitude and goodness. It's a crafted image, like any, and it may cause his enemies to roll their eyes, but it's also a product of his actions, years of work on behalf of the homeless, marshalling the creation of perhaps a hundred shelters throughout Toronto, constant demands for environmentally sound development, for affordable housing, for bike lanes and sidewalk cafés, for the sorts of things that constitute a tolerant and livable city. Those were Layton's issues, while others, people like councillor Doug Holiday, said the city should stick to worrying about the fiscal brickwork of policing and roads and sewers. In his first few months as leader of the NDP, by way of needling Paul Martin's supposed tax-dodging corporate mindset, Layton spent time championing, for heaven's sake, the Canadian flag. Less than a year on the job and he had already staked his claim as the defender of national pride. Where does that leave Stephen Harper, Belinda Stronach, et al?

You look for the seeds of this kind of instinct, the internal positioning system that helps Layton situate himself on the political landscape, and you go back to the village of Hudson, Quebec. The Laytons were well enough off—Jack's father, Robert, a community minded man devoted to the United Church, who would later become a federal Tory cabinet minister, was an engineer at the Montreal firm of T. Pringle and Son. Teenage Jack was alert, however, to the deep societal divisions between Anglophones and Francophones. The French kids he played hockey with didn't join the local swimming or boating clubs in which Layton was active. In fact, he says now, painting a vivid picture, while the Anglos frolicked in the pristine pool, the Francophones had to swim in the polluted Ottawa River. As Junior Commodore, de facto social convener for the boating club's youth group and budding social progressive, young Jack looked for an opportunity to bring the two sides together.

There was a youth group party in the works, with a rare live band, and Jack, already exhibiting a penchant for reading rule books, noticed that while most members were limited to bringing a single guest, the Junior Commodore could invite as many non-members as he wished. By his recollection, he signed in a hundred French kids that night, the youth group raised $3,000 for the club, and fun and fellowship prevailed. Jack says he saw the Northern Lights in the sky that night, the first time he'd seen them in Hudson. Who knows, there may even have been a heavenly chorus. It's no small part of Layton's retelling of this story—necessary, in fact, for maximum effect—that the next day the boat club's board, playing the role of right wing establishment, hauled him before an emergency meeting, ripped a strip off him, and disbanded the youth group.

[LINE BREAK]

It's natural, when you first meet Layton, to want to find the seam in the façade, the place where image gives way to lesser reality. Gradually it becomes clear that the front, though artfully lit, is integral to the whole. Layton's tendency to live and breathe his politics, take his policy to bed, as it were, has influenced even his marriages. His first wife, Sally Holford, with whom he had his two now grown children, Michael and Sarah, was a college sweetheart, but she wasn't keen on the kind of political existence Layton embraced. Olivia Chow, every bit as ideologically hard-wired as Layton, was a much better fit. Even their 1988 wedding on Ward's Island, by the water, with the skyline in the background, was designed (by committee, says Chow) to illustrate their shared ideologies and municipal dedication. Their choice of two gay ministers of the Unitarian Church, the reading of a poem declaring their commitment not just to each other but to the city and the environment, and their decision to have several friends rise and speak about issues important to them, such as the need for gays and lesbians to be able to express their devotion in such a ceremony—all these choices were born of a belief that politics was less a job than a lifestyle.

Not since Ronald Regan spoke of "Nancy and I" has a wife been tied so consistently and believably to one man's political effort. The "Olivia and I" that Layton makes frequent use of in speeches—both underlining and commodifying the relationship—reflects a real and fairly daunting political partnership. In talking about his marriage, Layton seems at pains to underline the conflict-free nature of their relationship ("We've never had an argument"), and even his sexual attraction to Chow ("I don't want to say anything wrong here, but she's got great legs!"). Still, there can be no doubting their effectiveness on council, where they acted as a kind of policy tag team, dividing up responsibilities in order to maximize their effort.

Chow, who has represented Trinity-Spadina since 1991, also acts as a calming influence. When Layton gets "a little too energetic" in the words of environmental lobbyist Gord Perks, "Olivia's the one person in the world who can say to him 'Jack? Earth to Jack. Put your feet back on the ground.'" Their home on Huron Street in the Annex is famous as a political action centre, where Svend Robinson's 1995 bid for the NDP leadership was launched, where activist groups have held meetings, campaign workers have manned banks of phone lines, and political thinkers have on quiet evenings thrilled to find themselves sipping merlot, eating brie and discussing strategy. "There's a cultishness that developed around Olivia and Jack," says city councilor Kyle Rae. "A little clique of the devoted. It was just like hanging out with royalty. They were very hallowed."

But though Chow's charm and intensity are impressive, it was the councilor with the famous mustache who had the drawing power. Talk to Jack Layton and you get the intoxicating sense of plugging into a continuous political current. In conversation, everything is referenced—this relates to that, which he worked on steadily for X number of years with so and so until such and such was achieved (bike lanes, sidewalk patios, a hundred shelters and group homes, the windmill by the lake …). The allusions and connections thread through a career that started when he won his first council seat in 1982 and continued through his mayoralty bid in 1991, his attempts at winning a federal seat in 1993 (against Bill Graham) and 1997 (against Dennis Mills), his switch from city council to Metro council and back again, his years on committees and boards and round tables, his triumphant year as president of the Federation of Canadian Municipalities—and every one of these references is tied to a battle fought, a vote won, a movement begun, until it seems irrefutable that Jack Layton, perhaps more than most politicians, lives for this.

GO Transit chairman Gordon Chong, who lost his council seat to Layton in 1982, hardly counts as a follower, but even he has to marvel. "Whenever there was a demonstration, or if he was able to plan a demonstration, he'd be there," says Chong. "Sometimes I was at home, watching TV news on a slow Sunday or something, 11 o'clock in the morning, and he's having a press conference over at Tent City or over at some other place when most politicians are glad to have a day off! I mean, the guy is 24 hours." While this reluctance to put his politics to rest is one that his colleagues find admirable, it's also fatiguing. "The Blackberry drives us all a little crazy at times," says Bruce Cox, Layton's national campaign director. "It used to be a joke during the leadership, you could tell when he got off an airplane, because all of a sudden the Blackberry would reconnect and the questions would come forward. The suggestions, the marching orders would suddenly come pouring out because he's just spent four hours on a flight and he's been madly typing away."

Since becoming leader, Layton has had the air of a man racing against time, or giddy with the chance to make the most of it, putting his drive to use in a promotional marathon of appearance making and attention grabbing that has had him speechifying across the country and pulling down serious TV time in counterpoint to seemingly every government manoeuvre. "It's mind boggling to me," says former NDP leader Alexa McDonough, echoing the standard sentiment. "People think I was a workaholic and I was intense, but I was nothing compared to this guy. It's breathtaking. He's indefatigable."

If it's true that this is the best of times for Jack Layton, the worst may have come more than a dozen year ago. In 1991, Layton ran for Mayor as the lone male and strident left-wing voice against June Rowlands, Betty Disero and Susan Fish. Having enjoyed the comforts of the Eggleton era, the city's right wing feared a Layton win and hauled out its heavy weaponry, calling him a leftist "looney" and painting his choice to live in co-op housing on Jarvis Street as a sneaky way to pay subsidized rents. Though the charges were false, he and Chow had to cope with staged protests outside their building. "There was a lot of red-baiting," says Layton's former ward-mate, Pam McConnell. "There was a lot of personalizing of Jack and Jack's life."

Even so, with conservative voter sentiment split amongst the women, Layton managed to briefly hold the lead in that race. But as the right positioned itself behind Rowlands, and the opposing candidates suddenly began to drop out—first Disero, then Fish—Layton was overrun. Decisively out of politics for the first time in years, he crashed emotionally; at least, that's how a colleague describes his reaction. The image doesn't sit well with Layton. He'll admit only to a month or so of being reluctant to get out of bed in the morning, and feeling, oh, a little grumpy. Whether or not this was depression, he looks back on it as "a weird experience." But then he put his mind to lifestyle politics, capitalizing on his sudden abundance of free time to work for the White Ribbon campaign fighting violence against women, and launching his own business, called The Green Catalyst Group, to encourage environmentally conscious development. And as soon as possible he got back in the game, first as a Metro councillor in 1994, then, in 1997, teaming up with Peter Tabuns against his old ally Pam McConnell for the two Don River seats on the first mega-city council. McConnell still shakes her head at this apparent betrayal—"outrageous," she calls it—but in the end she and Layton both won.

It was here, amid the new chaos of the combined council chambers, that Layton was at his maximizing best. Since his days studying political science at the feet of McGill University's Charles Taylor in the early 1970s, he had held dear Taylor's notion of dialectics—create a tension, then use it to produce a solution. In the new mega city, tensions sprouted like orchard apples. There were seven sets of bylaws to be rationalized, seven different systems for things like waste collection and snow removal. The workload on individual councillors was mind-boggling, and the ones who prospered were those, like Layton, Chow and Miller, who were willing—or had staffs willing—to pour through the numbing stacks of bureaucratic minutiae, looking for opportunities.

Unlike other councillors, whose staff helped deal with the day to day constituency work, Layton preferred to hire highly educated specialists in environmental and urban planning fields, who then worked closely with community activists to find and push agenda items. His office was a hive of political action, with Layton loading up on issues and leaving the details to his staff. Says Peter Zimmerman, a former Layton assistant, "You were doing sort of policy triage in Jack's office."

Lobbyist Gord Perks was one of those who worked closely with Layton's team, especially Franz Hartmann, Layton's point-man on the environment, who has since joined his Ottawa staff. "Franz and I would go through the council agenda and the committee agendas, which were literally feet tall," says Perks. "We would scan through them and see where the little tricks were." They would find, say, an obscure zoning bylaw in East York that Layton could leverage in an effort to change how garbage collection was run across the city. All he required was a quick summation. "You'd tell him in 10 seconds, and he'd get it," says Perks. "And he'd just quietly walk around council saying 'I've got this little issue, do you think I could get your vote on it?' and we'd just sneak stuff past the council." Layton, says Perks, could keep six different interpretations of an issue in his head, until he saw one that worked for everybody and gave him what he wanted. "And he just started putting together deal after deal after deal."

Layton also made a point of working with Mel Lastman and his city hall team lead by Andy Stein, presenting himself as a problem solver in the Taylorian tension between the Mayor's office and groups like the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty. "They were out in the streets, occupying buildings, taking over committee meetings, trying to actively embarrass the mayor," recalls Zimmerman. "And Jack was someone who could come to Andy Stein and the mayor and say, 'Hey look, here's how you can deal with these guys, and here's how you could advance an agenda, which is not going to be terrible from your perspective, but gets you out of a bind with these folks." It's worth noting that when a mob of poverty activists took over a council meeting in 1998 to demand that the City declare homelessness a national disaster, Layton is said to have been instrumental in guiding Lastman to a face-saving compromise. He was also accused (though he says the charge is "ridiculous") of having incited the demonstrators into the occupation in the first place.

To advance his agenda, Layton, with Chow's help, did his best to maximize the left-wing votes on council. This was not always appreciated, even by his supposed allies. "He would certainly attempt to keep us organized," says former councilor Ann Johnston. "I didn't like that. Not particularly. Cause I'm an individual, and I don't like being told what to do."

Gordon Chong now regards Layton's tactics with a mixture of admiration and chagrin. "He fervently believes in what he's doing, and if he feels his goal is a laudable goal then he doesn't care how he gets there." That includes sometimes acting in ways that contradict the high ground he's staked. "If you have to distort the truth a little bit, he's more than happy to do that."

A case in point might be the migration of the Gay Pride Day parade to Church Street. Layton has long been, in Kyle Rae's description, a "relentless" and "unqualified supporter of the gay and lesbian community." Indeed, to watch Layton, costumed fittingly in the cloak and top hat of a Victorian gentleman, walk down a closed-off Church Street on his traditional Halloween stroll is to see a man swarmed by well-earned affection. In 1984, during Layton's first term as councilor, Rae, then the director of the 519 Church Street community centre, was looking for a new venue for Pride Day celebrations. Previously the event had been held in Grange Park, until local residents had made their opposition clear. It was Layton who proposed closing off Church and holding it there instead. When the public works department objected, he conducted a poll of residents that he said showed support for the concept, and the motion was passed.

But there was more Layton craft in this support than people knew. He recalls with a wry grin just how he went about it. "The trick we did was, I notified a huge radius, like about 8,000 people. We had a hundred people who wrote in and said they thought they didn't like the idea of gays having the street closed for the day, and we had roughly an equal number writing back saying they thought it was good.

"So I reported to city council that—What's the ratio? An 80th?—that less than an 80th of the people were opposed. So that met the council policy of 75 per cent approval."

But while Layton and his staff happily focused on the big picture issues, they never cared much for local constituent concerns—the potholes, the parking issues, the day to day grunge work of most city politicians. When Layton ran for Mayor, he encouraged Kyle Rae to run for councillor in his old ward, and Rae now recalls the reaction he got from the constituents he met. "I would knock on the doors and people would say, 'You're replacing Jack? Oh, Jack never returned my calls. Jack never did this. Jack never did that.'" When it came time for Jack's old constituents to vote for mayor that year, says Rae, more of them voted for Rowlands than Layton.

It's probably for this reason, this long-established preference for the sweeping political gesture over the small local detail, and perhaps the fact that they had become generally fed up with him, that Layton's old colleagues on council think Jack is in a much better place now. "It's in the best interests of the property tax payer that he's off this council, definitely," says Doug Holiday. "He was a very expensive individual to have around here. He was very good at getting what he wanted."

These days, Layton spends much of his effort trying to maximize the impact of the tiny NDP caucus. Not surprisingly, the reports from inside are glowing. At first, admits Alexa McDonough, "there was a little skepticism by a couple of people." When Layton proposed, for instance, that caucus compose itself into groups of advocacy teams, not unlike the areas of specialty in his old council office, it recalled for a few members the sort of organization McDonough had tried to impose. "Yeah," Bill Blaikie is said to have grumbled, "I've seen this movie before."

But it seems Layton's version works. Perhaps because he's a harder, more impatient taskmaster than McDonough, quick to hold people accountable, Layton has achieved a remarkable turnaround in what was a notoriously fractious caucus. He's made decisive moves to reassign members—taking Svend Robinson out of his traditional job as foreign affairs critic, for instance, and transferring him to health, making Libby Davis the house leader, and giving Blaikie (who chose not to participate in this story) the job of parliamentary leader—and all of these moves have been well received. "He made very good decisions," says Davis. "I can tell you that the energy and the output has probably gone up tenfold. I'm not exaggerating. We're actually working as a team."

Typically, his scattershot approach—the relentless search for issues to tackle and banners to raise that necessitated his council staff's "triage"—is taking its toll on his federal staff, too. "He's so expansive, he's so energetic, he's so going in all directions," says McDonough, "that sometimes the demand that that creates for both staff and caucus members is excessive. It's like, 'Jack, you gotta stop for a minute…. Something's going to snap here.'" It's hard to say whether, after this initial sprint of activity leading up to a probable spring election, Layton will see the wisdom in adapting to a longer, steadier stride. But for now, his mad method has not only enticed star candidates like Ed Broadbent and others into the fold, it has given his party something it has lacked for decades: momentum.

Outside the House of Commons, next to the bust of Agnes McPhail, Layton waits, straight-backed as ever, with Chrétien's letter in hand. In the foyer, Karl Belanger watches the flow of media around the mics and grows anxious. As press secretary, Belanger is Layton's media wrangler, and the most intense 20 minutes of his workday starts a few minutes before three. It's then that he begins to drift from pool to pool, chatting with other press secretaries, listening to conversations among reporters, eavesdropping on interviews already underway, gauging where and when it's best for Layton to make his entrance.

There's no question which scrum he wants Layton to be in—it's the middle one now grilling Bill Graham about Mahar Arar because it's those reporters who are more likely to use a clip of Layton and his letter—but Graham is taking an exceptionally long time and the wait is nerve-wracking. There's always a chance the clutch of reporters could dissipate before Layton gets to be heard. A second minister could emerge to respond to an entirely different issue and, exuding the pheromone of power, lure reporters away just as Layton begins to speak. Or Layton could simply be blocked from the mic he wants by the suddenly in-the-way staff of another opposition leader.

"I've seen that happen," says Belanger. "It's like a basketball block. You're not supposed to do it, but if you do it it's not totally illegal."

Today, however, everything seems to go Layton's way. Because the foyer is crowded, Belanger positions Gail Dugas at a point where she can see both himself and Layton, and when Graham finally leaves the middle pool, he signals to Dugas, who relays the signal to Layton, who emerges looking confident and indignant about the prime minister's performance in the house.

"There's a false bravado today," he begins, holding up his prop to the lights. "It's belied by this letter. What we see from the prime minister is bravado and rhetoric and speeches and passion. What we don't see is action, when Canadian citizens are abroad in difficult situations…"

Layton's 12-question scrum goes about as well as he could have hoped. He blows his first reference to Syria, calling it Sweden by mistake, which requires a quick regroup. But over his years on city council Layton has honed the ability to rev up quickly to a state of purposeful agitation, to channel what might be called his "pop-up pique" in useful, agenda-furthering ways.

"…We see all kinds of pomposity, but we don't see action when it's required…."

The scrum lasts a total of five and a half minutes. And though it's hard to name one clear, crystal moment when demeanor, phrasing and well-lit prop align to create the perfect media moment, Layton squeezes more than anyone could reasonably expect out of two bland paragraphs on the Prime Minster's letterhead. At the end of it all, as the reporters drift away, one of them circles back and asks for a copy of the letter, which is surely a good sign.

But not everything is in Layton's control. He can maximize the devil out of a slim piece of paper, but that doesn't mean it's enough. As it happens, there's no shortage of news out of Ottawa this day—the lure of government ministers under fire is just the beginning, there's also the idea of Bono appearing at a Liberal convention, the spectacle of Chrétien being cheered by his caucus, and the bizarre image of a woman on icy Parliament Hill who, mid-afternoon, drove past security to the base of the Peace Tower and screamed that she was the reincarnation of Christ. In the face of all this, for once, Layton gets no media play from his efforts—neither his letter nor his repeated call for an inquiry get a single mention, either on the national news that night or in the major papers the next day.

But Jack Layton is never one to dwell on minor setbacks, and every new encounter is a new opportunity. That night, walking back from the Hill to the house of Layton's cousin, where he stays while in Ottawa, sleeping in a tiny slope-ceilinged room like a bachelor boarder, Layton encounters a small woman who approaches him and holds out a paper cup. Pushing his bike, he gives her a jolly "Hi!" and continues past.

In his 2000 book, Homelessness, written while he was vice-president of the FCM, Layton laid out reams of data and insight into the growing numbers of Canadians lacking shelter, and the ways in which he felt governments should respond. In his introduction, he wrote about walking home one wintry night with Olivia and passing by a prostrate homeless man, and the guilt he felt when the man was reported dead the next day. And although this night is not nearly so threatening, the woman seems in good health, and you or I or anyone else might very well do the same, it is an odd moment to see Canada's most powerful voice on homelessness walk by an outstretched cup.

Two, three, four steps Layton takes until he gets to the corner and stops, and then seems to register either that he has just passed a homeless person, or that he has just passed a homeless person in the presence of a journalist. He turns and calls to the woman now wandering off, "Don't go away." And as she makes her way back, he fishes for change. "I usually have some," he says, digging around. For an awkward moment, while I contribute the meagre contents of my pocket, it seems Layton is about to come up dry.

Then he finds one small coin. And Jack Layton, true to form, makes the most of it. He doesn't show the coin or drop it into the cup, he flings it down sharply like a dart so that it makes a loud pock!

"There you go!" he says, beaming an encouraging smile.

It's hard to tell if, on this occasion, his audience is impressed.

By Trevor Cole